By William Lestingi

For the last two decades games have tried to move closer to a form of interactive cinema , if not with gameplay certainly with storyline. Although most games have done little to try and move beyond the equivalent of B rated cinema, they have at the least tried to reproduce whole narratives and a certain continuity within the world each game is placed in. While this may work for many games there is something lost in the longevity and open ended state of an ip’s story and characters.

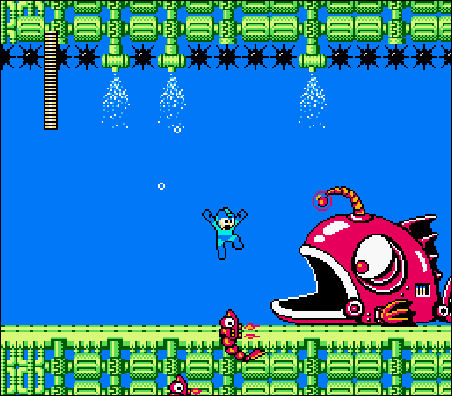

In the late 1980s and as early as 1986 with the NES, games started to shape some semblance of a storyline. None of these ran very deep on consoles but they had just enough to enact stories similar to episodic pulp movies or comic books. Megaman would forever fight Dr. Wily, Simon Belmont always with his whip entangled in a battle with Dracula. Plots had moved from “aliens invade” of the Atari era to having a reason for invading and a hero who went from a dot to having a name and history. The games however had enough freedom to change things up and there was a certain freedom to the possibilities based on a loose story format and comic book like narrative. What happens however, when you take 20XX and you place a real date on it? When you take the characters story and write a storyline in a realistic cinematic fashion with a clear cut beginning and a climactic middle inevitably you must come to an end. It may take place over the course of a few sequels but eventually the well runs dry. You can only pump out so many sequels in a film or book like narrative before you come to a conclusion and wrap it up. This then leads to another much maligned idea which has become just as relevant in film in the last few years…the dreaded reboot.

This isn’t to say that having a realistic narrative is bad, studios should however understand which ip’s should go this route and which should be more open. Square-Enix has been able to carry its Dragon Quest and Final Fantasy series by concocting a new world for each game with only certain factors and elements tying them together. Capcom has been able to hold a loose bit of canon with most of the games in the Street Fighter series while having non canon side games featuring the characters. It’s no surprise that the stats featuring the ages of all the characters that originally graced The World Warriors was later scrubbed making the characters timeless. Going this route has allowed the respective companies to make innumerable games starring the characters without hindering the continuity of a strict timeline or worrying about untied ends.

As the ability of developers to create photorealistic worlds becomes more and more a reality with the increase in technical capabilities, some artists may want to question whether they want their creations to come to an end in a realistic artistic statement or become an open ended expression to the culture they originally sprung from.

Good idea nuggets, let’s open this discussion up a little.

There’s a dichotomous disparity in the medium of videogames in regards to ‘the sequel’: as a computer program and ‘game’, subsequent iterations of a videogame series, whether connected narratively or not, improve in rules and simulation. Whereas as narratives, whether connected by rules and simulation or not, a videogame series will advance the plot and story of the world.

Games tend to arbitrarily hold onto their narratives when moving onto sequels: whereas really the main focus of the sequel is just to improve the mechanics and simulation.

Also, here’s a nice definition of terms: in film, ‘story’ is the background universe (i.e. whole world and characters and events and details) of the work, and ‘plot’ is simply the cause-and-effect chain of events that leads the reader through that story. ‘Narrative’ is simply the interweaving of story details that constitute the plot.